Unix man pages: AI-friendly documentation since 1971

Table of contents

Earlier this year, I mentioned man pages to a younger colleague and was surprised to discover he had never heard of them. This made me realize that time passes by, and things change. On second thought, maybe not so much.

How it all started

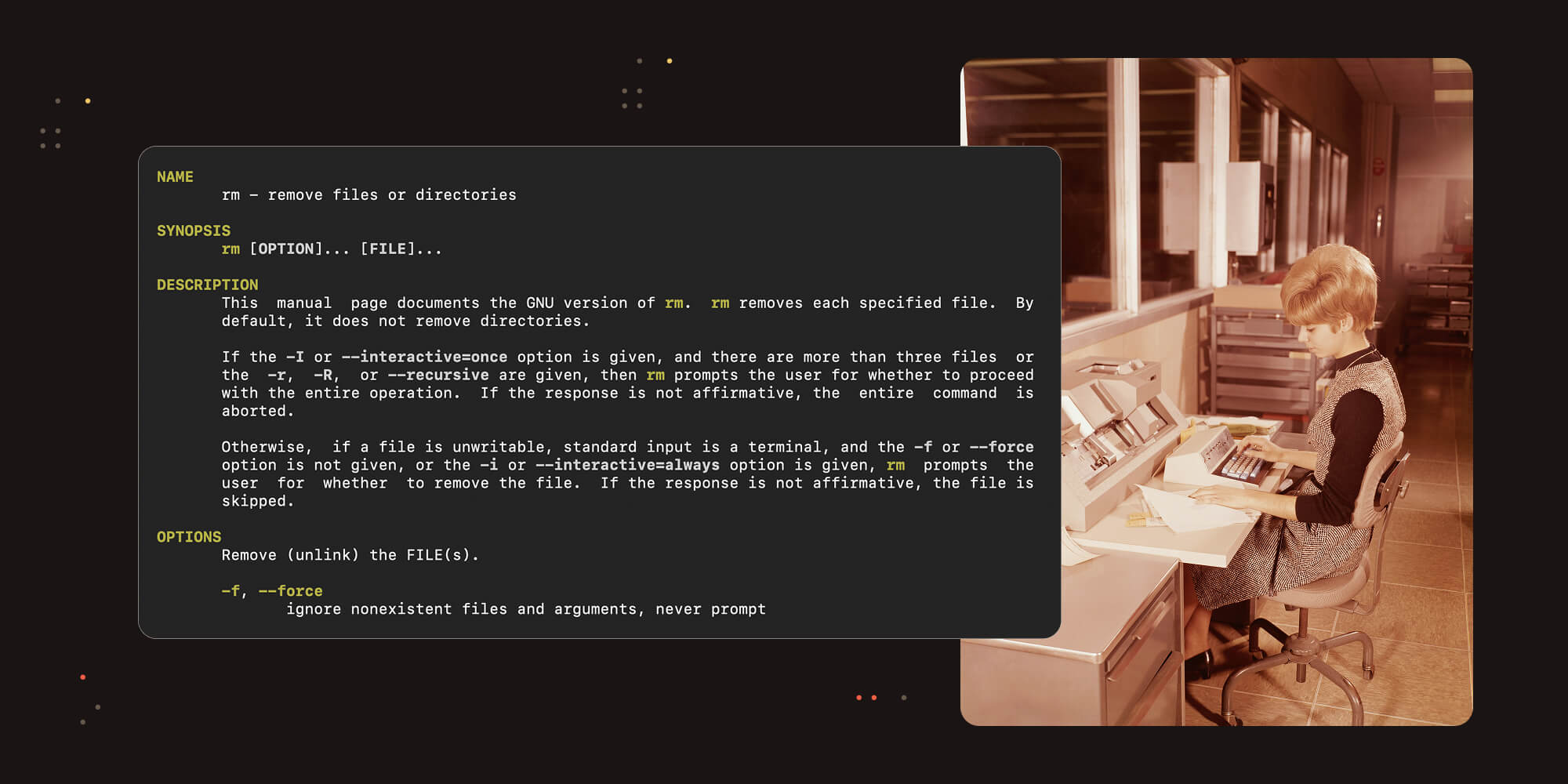

Traditionally, documentation for computers was printed on paper, or passed from master to disciple as spoken word. To look up a command argument or a system function parameter, one would have to go to the shelves, find the right binder, flip through pages, and hope it was up to date. And then, they’d get back to the computer, type the command or a piece of code, and hope again.

Although books about computer science and programming still exist, an alternative had already appeared in the early 1970s. One of the most notable examples was Unix Programmer’s Manual(opens in a new tab) (1971). It covered administration of the new operating system and functions of the similarly new programming language C. Its sections followed a strict structure, consisting of the following parts:

- Name — The name of the command or function.

- Synopsis — A brief description of how to use the command or function, including its arguments and options.

- Description — A more detailed explanation of what the command or function does, how it works, and any important notes.

- Files — A list of relevant files or directories associated with the command or function.

- See Also — References to related commands or functions.

- Bugs — Known issues or limitations of the command or function.

- Owners — The authors or maintainers of the command or function.

One could say that it was something like a new era in documentation. This format remains relevant, used by man pages (short for “manual pages”).

Both the Unix operating system and C language lived on, laying the foundation for a substantial part of modern IT. For example, this very website runs on Astro (more on how we got there), a JavaScript framework.

JavaScript is a descendant of C, although not many developers using our SDK ever experienced the original creation of Kernighan, Ritchie, and their colleagues.

Man pages

Likewise, man pages kept evolving, residing within distant descendants of Unix, such as Linux, FreeBSD, and macOS. For instance, Debian GNU/Linux has a policy(opens in a new tab) that requires all packages to include an associated man page for “each program, utility, and function.” This is a good example of colocating software with its documentation: a predictable way to find your way around some new utility.

Nowadays, man pages contain more entries while retaining the structural principles. Here’s an example of requesting a function man page in modern Ubuntu Linux:

$ man 3 strdupaThis post will touch upon what the 3 means further on, but the output will look like this:

NAME strdup, strndup, strdupa, strndupa - duplicate a string

LIBRARY Standard C library (libc, -lc)

SYNOPSIS #include <string.h>

char *strdup(const char *s);

char *strndup(const char s[.n], size_t n); char *strdupa(const char *s); char *strndupa(const char s[.n], size_t n);...

DESCRIPTION The strdup() function returns a pointer to a new string which is a duplicate of the string s. Memory for the new string is obtained with malloc(3), and can be freed with free(3).

The strndup() function is similar, but copies at most n bytes. If s is longer than n, only n bytes are copied, and a terminating null byte ('\0') is added.

strdupa() and strndupa() are similar, but use alloca(3) to allocate the buffer.

RETURN VALUE On success, the strdup() function returns a pointer to the duplicated string. It returns NULL if insufficient memory was available, with errno set to indicate the error.

ERRORS ENOMEM Insufficient memory available to allocate duplicate string....The command above will normally open a scrollable pager, such as less. To just print the output, you can prepend the command with setting the MANPAGER environment variable, like this:

$ MANPAGER=cat man 3 strdupaMan man

The interface to system reference manuals is called man, and it has a number of capabilities, such as searching for keywords, following references, and formatting. Naturally, this utility has a man page too. It can be retrieved with the following command:

man manThis will give you something like:

NAME man - an interface to the system reference manuals

SYNOPSIS man [man options] [[section] page ...] ... man -k [apropos options] regexp ... man -K [man options] [section] term ... man -f [whatis options] page ... man -l [man options] file ... man -w|-W [man options] page ...

DESCRIPTION man is the system's manual pager. Each page argument given to man is normally the name of a program, utility or function. The manual page associated with each of these arguments is then found and displayed. A section, if provided, will direct man to look only in that section of the manual. The default action is to search in all of the available sections following a pre-defined order (see DEFAULTS), and to show only the first page found, even if page exists in several sections....And then it will describe sections of the manual (the example with a library function above used section 3), and sections of the pages:

The table below shows the section numbers of the manual, followed by the types of pages they contain.

1 Executable programs or shell commands 2 System calls (functions provided by the kernel) 3 Library calls (functions within program libraries) 4 Special files (usually found in /dev) 5 File formats and conventions, e.g. /etc/passwd 6 Games 7 Miscellaneous (including macro packages and conventions), e.g. man(7), groff(7), man-pages(7) 8 System administration commands (usually only for root) 9 Kernel routines [Non standard]

A manual page consists of several sections.

Conventional section names include NAME, SYNOPSIS, CONFIGURATION, DESCRIPTION, OPTIONS, EXIT STATUS, RETURN VALUE, ERRORS, ENVIRONMENT, FILES, VERSIONS, STAN‐ DARDS, NOTES, BUGS, EXAMPLE, AUTHORS, and SEE ALSO.Note that it mentions man-pages page in section 7, which expands on the conventions for writing man pages, and the purpose of their sections. If you’re interested in exploring this further, the command would be:

man 7 man-pagesDeveloper experience retrospective

For decades, man pages were at the center of system administration and programming.

For example, in GNU Emacs (created in 1984), one would use the command M-x man to look up man pages(opens in a new tab) directly from the editor. In ViM (first released in 1991), a popular plugin would enable the :Man command.

Both editors are used and loved by many (albeit rarely by the same people) — also here at Nutrient. And when in a terminal, natural routines relied on man command lookups. I, personally, still have this habit.

Then, access to the internet became common. Search engines got clever (does anybody remember AltaVista?). Typing a set of keywords into the search bar became an alternative. The verb “to google” appeared.

Furthermore, the nature of search has changed. Instead of looking up a function or a command, developers are looking for a more complete solution (e.g. “How to make a PDF viewer in React?” or “How to balance load in distributed systems?”).

Of course, pure documentation lookups are still common, especially for service interfaces and SDKs (e.g. Document Engine API). However, searching in a web browser is annoying, and developers prefer their tools to find things for them. This creates space for common formats, such as OpenAPI, AsyncAPI, and others. Schemas (e.g. Helm value schemas like this one(opens in a new tab)) are now also considered by IDEs, allowing them to provide autocompletion and validation.

But the bulk of documentation is written in free form and layout, in different formats (even though one of them is Markdown). It makes perfect sense for humans; documentation user experience (UX) plays a significant part in the competition of frameworks, libraries, and SDKs. Layout is driven by audience preferences. It must be convenient and pretty.

Consequently, the layout is also domain driven. In the wake of advances in the World Wide Web, documentation websites became more websites than documentation. Evolving in many different directions, pretty much like life forms during Cambrian radiation(opens in a new tab), they took many different shapes. Today, manuals for embedded systems look very different from web framework references or satellite data interface control documents.

All this happily evolved and worked fine.

Until it was over — and it became possible to have a natural dialog with a computer without opening the web browser. This pattern suddenly brings us back to the times of sophisticated Emacs and ViM configurations: Knowledgeable wizards spent hundreds of hours tuning their editors to predict their thoughts and provide the right information at the right time.

Now, everybody can do it — as long as the AI model is capable enough.

What changes with AI

Machines have different needs. They don’t care about fonts and colors, but they want structure.

Modern AI models are getting better and better at reading and understanding arbitrary text, but it’s still hard for them, wasting both time and tokens.

I asked Claude Code (an agentic coding tool from Anthropic): “Why is it harder for you to study unstructured guides?”. Here are highlights from its answer, direct quotations, just slightly restructured:

Claude Code finds unstructured guides more challenging for several key reasons:

Context Window Limitations. Unstructured guides often bury critical information in lengthy narratives. When a guide mixes setup instructions, conceptual explanations, troubleshooting, and examples all together, Claude has to process much more text to extract specific actionable information.

Ambiguous Information Hierarchy. In unstructured documentation, it’s unclear what’s essential vs. supplementary. A tutorial might spend 3 paragraphs on background context before mentioning a critical prerequisite buried in the middle.

Mixed Content Types. Unstructured guides often combine: historical context, conceptual explanations, step-by-step instructions, troubleshooting tips, and personal opinions/recommendations. This makes it harder for Claude to distinguish between “what you need to do” vs. “why this exists” vs. “what might go wrong.”

Inconsistent Formatting. Without standardized sections, every guide organizes information differently. One might put examples at the end, another sprinkles them throughout, a third puts them in sidebars. Claude has to adapt its parsing strategy for each document rather than applying consistent patterns.

Missing Cross-References. Unstructured guides might mention related topics in passing but don’t provide systematic cross-referencing.

And here’s what it thinks about man pages:

With man pages’ structured sections, Claude can quickly identify the SYNOPSIS for syntax or EXAMPLES for usage patterns.

Man pages’ rigid structure (NAME → SYNOPSIS → DESCRIPTION → OPTIONS) creates predictable information hierarchy that Claude can navigate efficiently.

Man pages include explicit “SEE ALSO” sections that help Claude understand relationships between commands and concepts. This is why documentation formats like OpenAPI specs, JSON schemas, and yes—50-year-old man pages remain so valuable for both humans and AI tools. The structure itself is information.

Apparently, Claude Code would feel fine at Bell Labs 50 years ago?

What now?

Should we rewrite all manuals using groff(opens in a new tab) to make LLMs happy? What will happen to the beautiful documentation websites that companies (including Nutrient) are so proud of? And where does that leave SEO?

Or should we hope that AI will get enough cognitive power to understand what we write and ignore the heat generated by the servers powering it? But then, is there a reason to keep websites at all?

The notion of “helping” AI understand documentation isn’t new. There are a number of practices gaining popularity, such as “clues” for LLMs, CLAUDE.md files, and others.

About that. Remember man man? A man page about reading man pages. Similar, is it not?

There will be an open ending: I don’t have a definitive answer about the optimal strategy for documentation henceforth. However, it’s worth contemplating that half a century ago, Unix creators managed to set an AI-friendly documentation standard.

Maybe it’s not exactly the new era for Emacs and man pages. But the fact that the most innovative way of software development has so many similarities with forgotten routines of the past is a reminder that there may be a lot to learn from the past.

If you have any thoughts on this, consider tagging me on LinkedIn(opens in a new tab), and let’s discuss it.