High performance UI using web workers

Table of contents

Web workers(opens in a new tab) have been around for more than a decade, but they’re often overlooked as a solution for user interface (UI) performance problems. Most developers think of them as tools for background data processing or API calls, and not for making user interfaces more responsive.

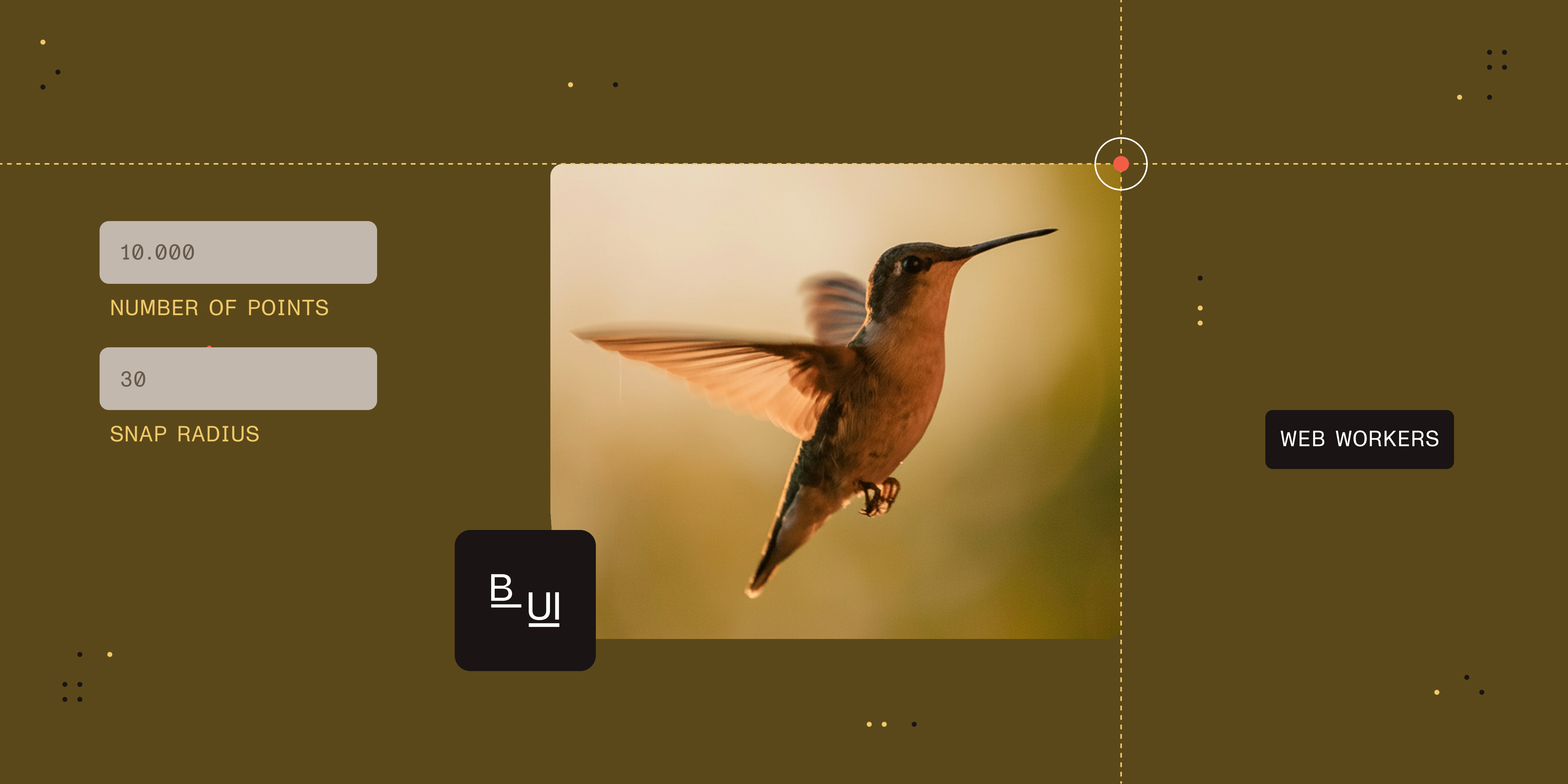

This article explains web workers through a practical example: Imagine you’re building an application where users can click on points of interest. You want the cursor to “snap” to nearby points for precise selection; when the user hovers near a point, it should automatically highlight the closest one within a specified radius.

This is exactly what we built with the PointPicker component(opens in a new tab) from our design system, Baseline UI(opens in a new tab). PointPicker allows users to select coordinates on a canvas, and we wanted to add snapping functionality so the cursor automatically highlights the closest point within a specified radius.

What starts as a simple feature request — “make the cursor snap to nearby points” — becomes a perfect demonstration of how web workers can transform user experience.

The example shows how to recognize when your UI operations are CPU-intensive enough to benefit from parallel processing, and how to architect solutions that move the right work to background threads.

The problem: When simple gets complex

The video above shows the PointPicker component with the snapping functionality we built. The green dots are the snapping points, and the red dot is the current snapped point. The video includes 100,000 points.

The link to the live demo is here(opens in a new tab).

Building snapping functionality sounds trivial. Calculate distances on mouse move, find the nearest point, and highlight it. Done.

At first, we tried the obvious approach: Calculate the distance from the cursor to every point, find the closest one within our snap radius, and highlight it. When the cursor is within the specified radius of a point, it “snaps” to that point, providing visual feedback and making precise coordinate selection easier.

This worked perfectly with 100 points. But when we scaled up to thousands of points, the simple distance calculation became a performance bottleneck. Every mouse movement triggered hundreds of calculations, all competing with the UI thread for attention. The cursor started feeling sluggish, UI updates became delayed, and users noticed something was wrong.

The main thread was drowning in math while trying to handle rendering, event processing, and user interactions. Something had to give.

The discovery: Spatial indexing

We needed a better approach. After researching spatial data structures, we discovered spatial indexing. Instead of checking every single point with O(n), we could use a spatial data structure to find nearby points much faster.

We chose KDBush(opens in a new tab), a flat K-D tree implementation that can find all points within a radius in O(log n + k) time, where k is the number of results found. For small snap radii, k is typically very small, making this dramatically faster than the O(n) brute force approach.

The web worker solution

But even with spatial indexing, the calculations were still blocking the main thread. That’s where web workers come in: They let you run heavy calculations in a background thread. The main thread stays free for UI work, while workers handle the computational heavy lifting.

The architecture

We designed a two-tier system:

- Main thread — Pure UI, with events, animations, and user interactions

- Proximity worker — Spatial indexing, with KDBush(opens in a new tab) and distance calculations

The combination of spatial indexing and workers creates a complete solution: fast algorithms running in parallel threads.

Worker communication

Worker communication traditionally involves manual message passing, which can be verbose. We used Comlink(opens in a new tab) to simplify this — it makes worker calls feel like regular function calls, but the core concepts apply to any worker communication approach.

The proximity worker

Here’s our worker that handles spatial indexing with KDBush and distance calculations:

import KDBush from "kdbush";import { expose } from "comlink";

interface Point { x: number; y: number;}

class PointProximityWorker { private index: KDBush<Point> | null = null; private snapRadius: number = 50;

buildIndex(points: Point[]): void { // KDBush construction: O(n log n) — one-time cost. this.index = new KDBush( points, (p) => p.x, (p) => p.y, ); }

setSnapRadius(radius: number): void { this.snapRadius = radius; }

findNearest(x: number, y: number): Point | null { if (!this.index) return null;

// `KDBush.within()` finds all points within the snap radius - O(log n + k), where k is results found. const nearby = this.index.within(x, y, this.snapRadius); if (nearby.length === 0) return null;

// Find the closest point among the candidates. let nearest = nearby[0]; let minDistance = this.calculateDistance(x, y, nearest);

for (let i = 1; i < nearby.length; i++) { const distance = this.calculateDistance(x, y, nearby[i]); if (distance < minDistance) { minDistance = distance; nearest = nearby[i]; } }

return nearest; }

private calculateDistance(x: number, y: number, point: Point): number { return Math.sqrt(Math.pow(x - point.x, 2) + Math.pow(y - point.y, 2)); }}

expose(PointProximityWorker);React integration

This section will show how to integrate the worker with React: by creating a custom hook for the worker, and then using it in our component.

The custom hook

First, we create a hook that manages the worker lifecycle:

import { wrap } from "comlink";import { useEffect, useRef, useState, useCallback } from "react";

interface Point { x: number; y: number;}

interface PointProximityHook { findNearest: (x: number, y: number) => Promise<Point | null>; isReady: boolean;}

export function usePointProximity( snapPoints: Point[], snapRadius: number,): PointProximityHook { const workerRef = useRef<any>(null); const [isReady, setIsReady] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => { const worker = new Worker( new URL("./PointProximityWorker.ts", import.meta.url), { type: "module" }, );

const workerApi = wrap(worker); workerRef.current = workerApi;

workerApi.buildIndex(snapPoints); workerApi.setSnapRadius(snapRadius); setIsReady(true);

return () => { worker.terminate(); }; }, [snapPoints, snapRadius]);

const findNearest = useCallback( async (x: number, y: number): Promise<Point | null> => { if (!isReady || !workerRef.current) return null; return await workerRef.current.findNearest(x, y); }, [isReady], );

return { findNearest, isReady };}The component

The final component is clean, but there are some gotchas:

import React, { useState, useCallback } from "react";import { usePointProximity } from "./usePointProximity";

interface Point { x: number; y: number;}

interface PointPickerContentProps { snapPoints: Point[]; snapRadius: number; onPointSelect: (point: Point) => void;}

export function PointPickerContent({ snapPoints, snapRadius, onPointSelect}: PointPickerContentProps): JSX.Element { const [cursorPosition, setCursorPosition] = useState<Point | null>(null); const [snappedPoint, setSnappedPoint] = useState<Point | null>(null);

const { findNearest, isReady } = usePointProximity(snapPoints, snapRadius);

const handleMouseMove = useCallback(async (event: React.MouseEvent<HTMLDivElement>) => { const rect = event.currentTarget.getBoundingClientRect(); const x = event.clientX - rect.left; const y = event.clientY - rect.top;

setCursorPosition({ x, y });

if (isReady) { const nearest = await findNearest(x, y); setSnappedPoint(nearest); } }, [findNearest, isReady]);

return ( <div onMouseMove={handleMouseMove}> {/* Any component that can use the proximity data */} <SomeVisualComponent points={snapPoints} activePoint={snappedPoint} /> </div> );}The transformation

The results were dramatic. The interface felt much more responsive — the cursor moved smoothly, UI updates happened without delay, and users could interact with thousands of points seamlessly.

Before — Every mouse movement triggered O(n) calculations that blocked the main thread.

After — O(log n + k) calculations ran in a background thread.

The key insight is that the main thread is now completely free to handle user interactions — no more competing for attention between calculations and UI updates.

What started as a performance problem became a demonstration of how web workers can improve user experience.

You can see the web worker-powered PointPicker with snapping functionality in action in our live demo(opens in a new tab).

The broader impact

This point picker example demonstrates a fundamental shift in web development thinking. Instead of optimizing single-threaded code, we’re leveraging parallel processing.

The pattern applies to many other scenarios:

- Real-time data visualization

- Complex form validation

- Image processing and manipulation

- Large dataset filtering

- Game logic and physics calculations

Lessons learned

- Spatial indexing is crucial — Without KDBush, workers alone wouldn’t solve the O(n) brute force problem.

- Communication overhead is manageable — For CPU-intensive tasks, the worker communication cost is negligible.

- The main thread stays responsive — Workers keep the UI thread free for user interactions.

- Architecture matters — Spatial indexing and workers create a complete solution.

- Start simple, then optimize — Basic calculations → KDBush → workers

Conclusion

The point picker component demonstrates that web workers can transform sluggish UI components into responsive, scalable solutions. But they’re not a panacea — they require careful consideration of tradeoffs and proper implementation.

The key insight is recognizing when your UI operations are CPU-intensive enough to benefit from parallel processing. For the right use cases, web workers can make the difference between a broken feature and a delightful one.

The question isn’t “Can I use web workers?” Rather, it’s “Should I use web workers?” The answer depends on your specific performance requirements and user experience goals.